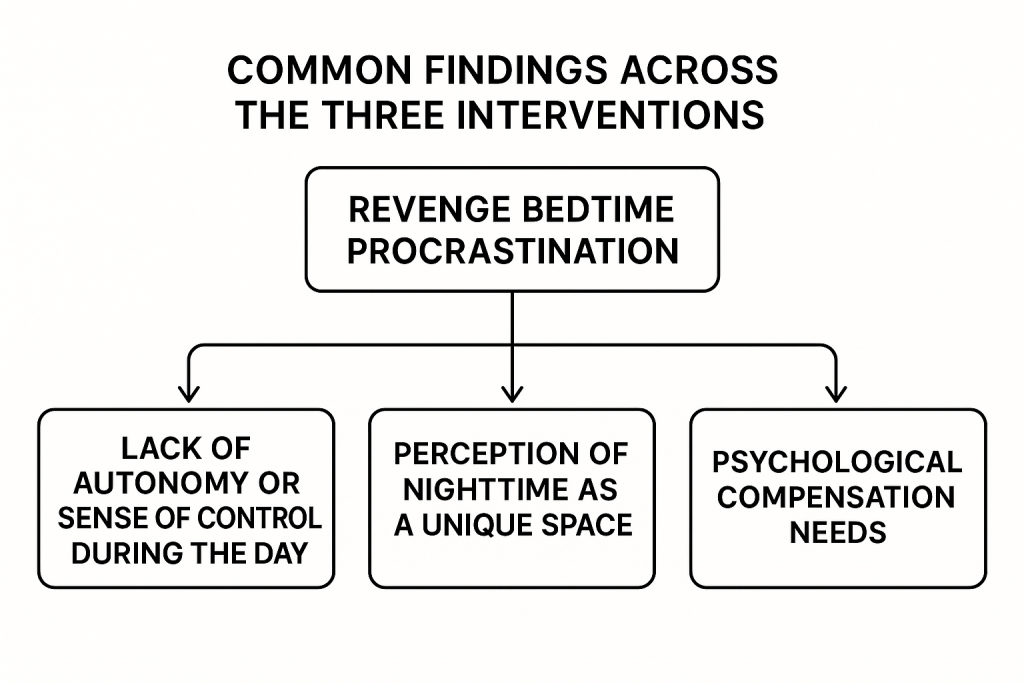

Common Findings from the Three Interventions:

1. The core driver of Revenge Bedtime Procrastination is not “lack of sleep,” but “lack of autonomy and control.”

When individuals are able to experience personal time, autonomy, or a respected rhythm during the day, the urge to stay up late decreases.

However, if daytime continues to feel externally controlled or overly structured by others, nighttime is still perceived as the only space where they can reclaim agency.

2. “Daytime freedom” is not psychologically equivalent to “nighttime compensation.”

Even when free time is scheduled during the day, many participants reported that it does not provide the same emotional quality as nighttime.lacking feelings of safety, solitude, and being undisturbed.

Nighttime compensation carries a special psychological texture: it feels ritualistic, private, and functions as an emotional safe zone

Summary:The satisfaction of Revenge Bedtime Procrastination does not lie in the length of time, but in “psychological space + autonomy + a sense of identity that is not disturbed”.

From Observation → Intervention → Mechanism Validation

| Stage | Previous Research Focus | Current Research Focus |

| Awareness | Daily Rhythm Record → Record emotions & time rhythm awareness | Identified that daytime time is compressed; nighttime becomes a compensation outlet |

| Behavior Trial | Sleep Transfer + Self-Control Schedule | Tested whether compensation can shift to daytime or earlier hours |

| Mechanism Intervention (Current) | Can nighttime satisfaction be advanced or reconstructed through psychological + time perception intervention? | Further validation: Is staying up late driven by autonomy needs or by the irreplaceable nature of nighttime itself? |

From Surface Phenomena to Underlying Mechanisms

Shared conclusions across the three interventions:

·Staying up late is not driven by the pursuit of “more time,” but by the need for psychological compensation, a sense of control, and identity.

·Even when free time is available during the day, it lacks the emotional atmosphere and psychological exclusivity of the night.

·Improving self-discipline does not necessarily reduce bedtime procrastination, suggesting that this behavior is not merely an issue of willpower.

The new intervention therefore asks:

Is the unique satisfaction of nighttime derived from time itself, or from the psychological perception that “this time belongs to me”?

To test this, participants are allowed to engage in leisure activities earlier, without knowing that the actual time has been altered.This allows us to examine:

If they still feel satisfied → nighttime is replaceable, and the essence lies in autonomy

If they remain unsatisfied → nighttime carries an irreplaceable psychological quality

Intervention Plan: Psychological and Temporal Perception Intervention for Revenge Bedtime Procrastination

1. Research Objective

This study aims to explore whether Revenge Bedtime Procrastination is driven by a conscious psychological need (“staying up for the sake of staying up”) or by a subconscious habitual response. It further tests whether adjusting time perception and circadian rhythm alignment can reduce the negative effects associated with Revenge Bedtime Procrastination.

2. Theoretical Foundation

Definition of Revenge Bedtime Procrastination:

Revenge Bedtime Procrastination refers to the deliberate delay of sleep despite knowing one must wake up early the next day, as a way to compensate for lost “autonomous time” during the day. Its essence lies in psychological compensation for a lack of control.

Distinguishing conscious satisfaction from subconscious behavior:

If participants still feel satisfied after going to bed 2 hours earlier, it suggests that satisfaction primarily arises from perceived control and time awareness, not the late-night itself.

If participants feel unsatisfied despite going to bed earlier, it implies that Revenge Bedtime Procrastination is more of a subconscious psychological defense mechanism.

Theoretical support:

Advancing bedtime by 1–2 hours is physiologically supported (AASM, 2017), while advances up to 3 hours remain within an adaptable range without causing circadian misalignment (Harvard Medical School, 2015).

https://aasm.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/07/Review_CircadianRhythm.pdf?

3. Experimental Design / Intervention Framework

Experiment:

Participants’ sleep times are advanced by 2 hours (based on their natural circadian rhythm) without informing them of the time change. The aim is to test whether subjective satisfaction can still be achieved when sleep occurs earlier.

(Intervention idea: To prevent lateness, the perceived time is shifted forward — how does this change affect bedtime satisfaction?)

Control conditions:

Participants are unaware that the actual time has been advanced.

Their baseline sleep and wake times are recorded before the intervention.

4. Intervention steps

Step 1: Subjective Recording

Collect data on participants’ typical routines, nighttime motivations, and perceived sense of control.

Step 2: Intervention Execution

Participants are informed that they are taking part in a study on “sleep and time perception” and sign a written consent form.

To maintain ecological validity, participants know they will receive an intervention but are not told its exact form or timing.

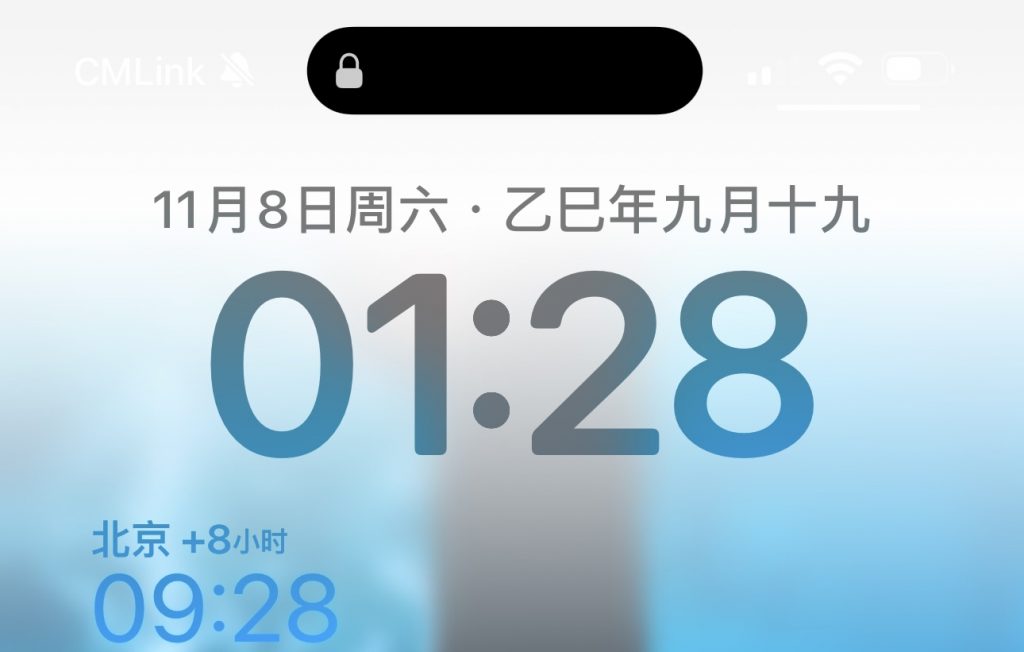

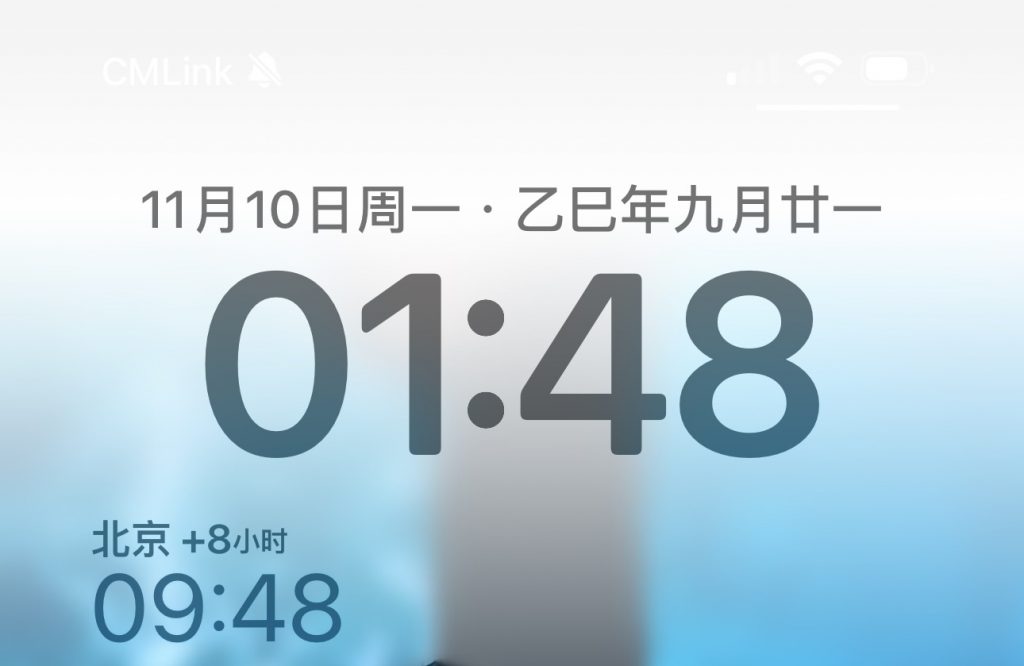

With consent, researchers conduct supervised overnight observation in participants’ homes and temporarily adjust the system time on their devices (without affecting any personal data or communication functions).

After participants fall asleep, short video documentation (non-identifiable, privacy-protected) is taken only to verify sleep onset.

Following the intervention, participants receive a full debriefing explaining the study’s design, purpose, and the time manipulation, and reconfirm their consent for data use.

Step 3: Interview and Data Analysis

Compare participants who felt “satisfied” vs “unsatisfied” after the intervention.

Explore underlying psychological compensation needs (autonomy vs emotional release vs achievement).

5. Application of Findings

For individuals with RBP tendencies:

→ Use time illusion and behavioral substitution to help participants experience a sense of nighttime autonomy earlier in the evening.

For habitual night owls:

→ Apply habit disruption and circadian training to strengthen sleep consistency and promote stable early sleep patterns.

How to get in touch with stakeholders and participate:

Participant 1

Participant 2

Participant 3

Participant 4

The video was shot at 1:25 a.m. and the participants might have fallen asleep about 20 minutes before that. After seeing the lights in the participants’ rooms go out, I entered the room to shoot a video after a while.

Participant 5(Participants found that the time was advanced during the experiment, so the experiment was interrupted)

Intervention Analysis Report

1. Research Objective

This intervention aimed to examine whether the satisfaction, autonomy, and perceived “nighttime ownership” associated with Revenge Bedtime Procrastination would change when participants were guided to fall asleep earlier without being aware of the exact time manipulation.

The study explored:

Whether the gratification of Revenge Bedtime Procrastination comes from objective nighttime hours,or from subjective temporal ownership,or from habitual, emotional, or atmospheric factors of the night.

This intervention introduced a controlled manipulation of time perception to distinguish between these mechanisms.

2. Participant Characteristics (Based on Four Documents)

2.1 Irregular Sleep Patterns

All participants reported irregular sleep schedules, typically falling asleep between 00:00–04:00, consistent with known Revenge Bedtime Procrastination patterns.

2.2 Universal Late-Night Phone Use

Every participant engaged in nighttime smartphone activities:

short video browsing

streaming episodes

social media scrolling

2.3 Two Major Motivations for Staying Up Late

(1) Compensatory autonomy

Need for personal free time after a controlled daytime schedule

Night as the only “owned” time

(2) Habitual / Emotional soothing

Comfort in nighttime ambiance

Emotional decompression

3. Key Findings

Two Distinct Types of Revenge Bedtime Procrastination Identified:

| Type | Satisfaction Maintained | Unfulfilled After Early Sleep |

| Cause | Desire for personal time | Atmospheric + emotional dependency |

| Night Attachment | Low | High |

| Replaceability | High | Very low |

| Role of Time Perception | Strong | Moderate |

| Awareness of Manipulation | None | Some suspicion |

① Replaceable-Type (Behavioral)

Driven by:

Need for personal time

Compensatory autonomy

Characteristics:

Nighttime itself is not essential

Satisfaction can be substituted

Earlier sleep + simple rituals work well

Outcome:This group remained satisfied even with shifted bedtime.

② Non-Replaceable-Type (Emotional–Habitual)

Driven by:

Attachment to nighttime atmosphere

Emotional decompression

Entrenched late-night routines

Characteristics:

Night carries symbolic meaning (“my real time”)

Strong need for solitude and quiet

Early sleep feels like “loss of control”

Outcome: Satisfaction drops significantly after early sleep.

4. Effectiveness of Time Manipulation

Participants’ Awareness:

4/5 did not detect the time shift

1/5 noticed only “time felt fast,” not the manipulation

Implication:

Covert time perception adjustment is feasible and effective

Successfully reveals deeper psychological structures of Revenge Bedtime Procrastination

5. Implications for Intervention Design

Revenge Bedtime Procrastination is not homogeneous ,two subtypes require different strategies.

For Replaceable-Type:

Use early sleep + structured rituals

Reinforce autonomy through pre-sleep activities

For Non-Replaceable-Type:

Provide emotional regulation tools

Increase daytime “pocket time”

Introduce alternative decompression routines

Gradually break nighttime habits

6. Core Insight

Subjective ownership of time,not objective clock hours is the key psychological driver of Revenge Bedtime Procrastination.

This intervention demonstrates a new method:

→ Changing behavior through altering perceived time.

Leave a Reply