During the continuous research intervention, I have been pondering over the following several questions:

1. Your question and intervention: how do they interact?

My research question:

How can behaviour created by a loss of autonomy over work-life balance be mitigated, to help young Chinese people avoid seeking late-night activities as compensation for the loss of agency in their daytime schedules?

Core focus:

What psychological mechanisms drive Revenge Bedtime Procrastination ?

Can improving daytime autonomy and rhythm reduce night-time compensatory behaviour?

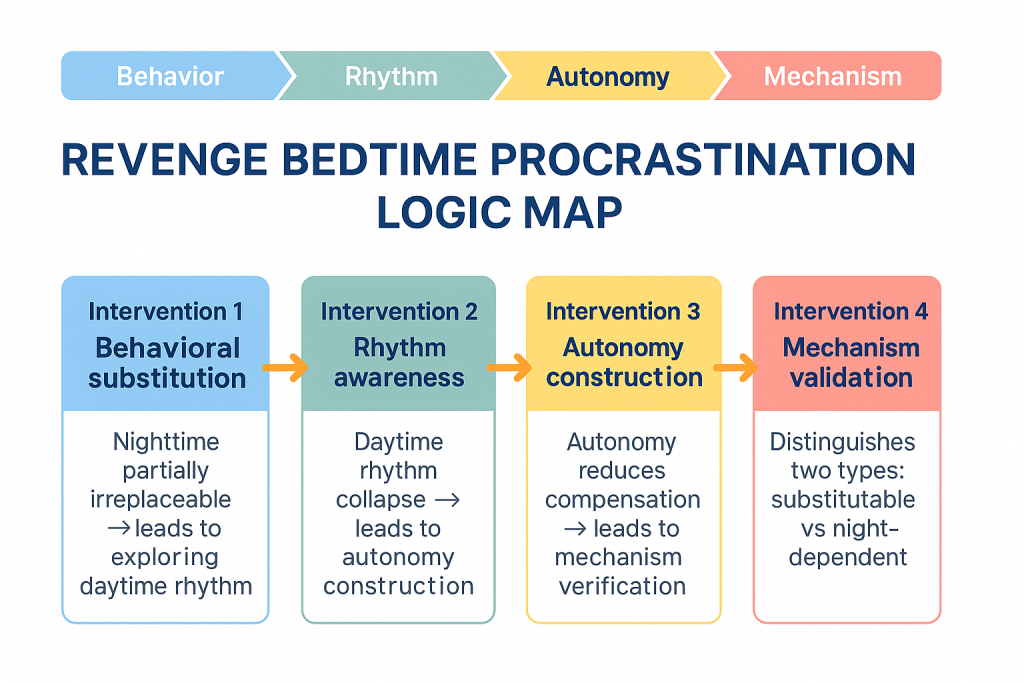

How the four interventions interact:

The four interventions are not separate,they form a progressive logical chain:

Intervention 1 Behavioural level:

Tests whether night-time compensation can be replaced.

Intervention 2 Cognitive level:

Examines how awareness of one’s daily rhythm affects Revenge Bedtime Procrastination .

Intervention 3 Autonomy construction:

Tests whether enhancing daytime autonomy reduces compensatory behaviours.

Intervention 4 Mechanism verification:

Differentiates two types (replaceable / non-replaceable).

Progression logic:

behaviour → cognition → autonomy construction → mechanism verification

2. Your stakeholders: who are they? Why? How are you interacting with them?

Who:

a. College students (20-24)

Characteristics: The academic and exam pressure is relatively high, and the daytime is often occupied by courses, homework and social activities.

b. Youth Workers (24-28)

Characteristics: Working at high intensity for long periods during the day, and personal time is highly controlled.

Why:

The survey shows that 52% of college students go to bed after midnight, and 19% go to bed after 2 a.m.Their behavioris an overcompensation, using late nights to ease discomfort or boost a sense of superiority. It strongly reflects core psychological motivation of compensation.

The Philips Global Sleep Survey pointed out that more than 50% of young workers go to bed after midnight, and 13% go to bed after 2 a.m. Young workers consumed by high-intensity work, so they rely on staying up late to regain personal identity and value.Their behavior of Revenge Bedtime Procrastination is closely related to a lack of autonomy,aligning with the focus of this research.

Interaction methods:

·Daily logs

·Rhythm perception cards

·Pre/post interviews

·Real feedback during interventions

3. What evidence are you gaining, and how?

Evidence sources:

Behavioural & emotional logs

Daily rhythm records (morning / afternoon / night)

Interviews (before and after interventions)

Autonomy-experience evaluations

4. Are the goals of your research clear and SMART?

S-Specific:

Explain psychological mechanisms of Revenge Bedtime Procrastination; test whether daytime autonomy and rhythm reconstruction reduce Revenge Bedtime Procrastination.

M-Measurable:

Measured via logs, rhythm cards, sleep time changes, emotional state scores.

A-Achievable:

All four interventions are feasible, operational, and sustainable for participants.

R-Relevant:

Strongly related to time anxiety, youth mental health, and behavioural compensation patterns in modern society.

T-Timely:

Interventions and evaluations conducted within a defined time frame.

5. Recent reality check?

Yes. Through reflection, I realised:

Daytime autonomy cannot fully replace the symbolic meaning of night time.

Some participants have emotional or habitual dependence on the night short-term interventions may not change this.

As a researcher, my own rhythms, biases, and emotional states influence the process; continuous reflection is necessary.

6. Am I building the right network?

Yes. My research network includes:

Youth participants → providing real lived experiences and diverse perspectives.

Sleep-research sources → academic literature, reports, surveys.

Psychological frameworks → autonomy theory, time perception, behavioural compensation.

Tutorials & seminars → refining methodology, validating insights, and supporting reflective practice.

Reflection:

1. Initial Observation: Where Did the Research Begin?

This research began with a recurring observation: first from my own experience, and later from conversations with friends. I noticed that many people intentionally extend their night-time hours to regain a sense of personal ownership over their time. Friends would often say things like, “Only when I stay up late do I feel like I’m actually living,” or “I don’t care if I’m tired tomorrow—I just need a bit of time for myself tonight.”

These real conversations made me realize that Revenge Bedtime Procrastination is not caused by laziness or lack of self-control. Rather, it emerges from accumulated daytime pressure and unmet emotional needs. I did not merely view it as a behavioral pattern, but rather discussed with the participants the psychological, emotional and intrinsic driving factors that shape retaliatory staying up late.

This led me to design a series of interventions that allowed participants not just to describe their night-time habits but to experience and reflect on them.

2. Designing Interventions as Research Tools

I designed four interventions, each from a different perspective, allowing me to enter participants’ daily routines and collect ongoing reflections. The interventions revealed not only behaviour but also rhythm, emotional states, and underlying needs.

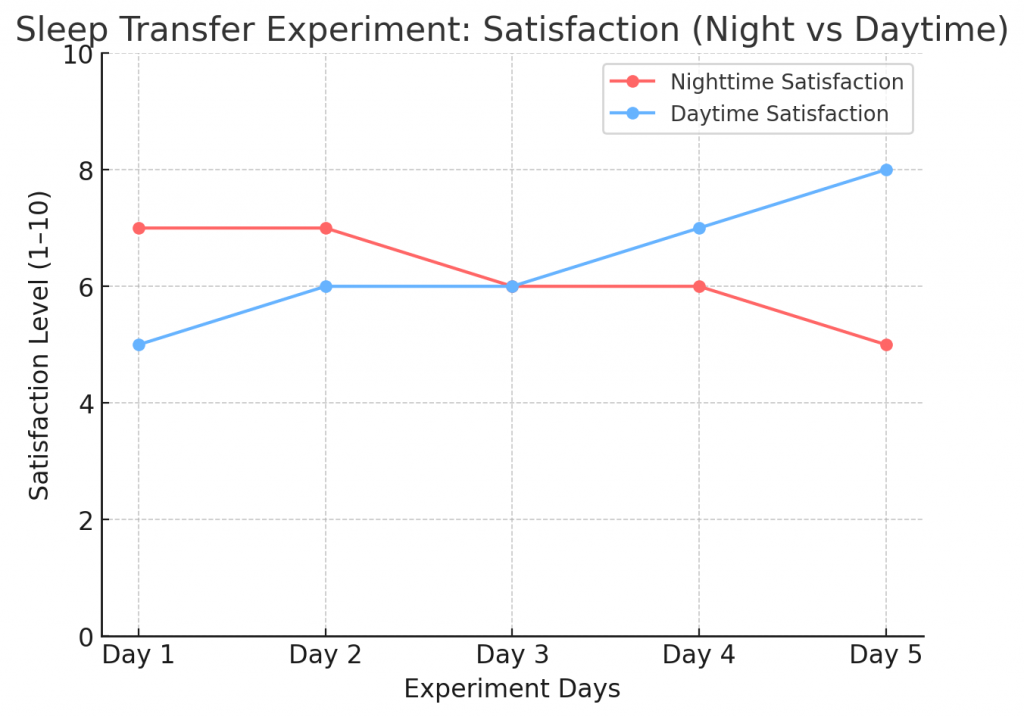

Intervention 1 — Sleep Transfer Experiment:

Shifting “compensation” from late night to daytime

This tested whether satisfaction could be moved from night to day, revealing the emotional and symbolic meaning of the night. Participants consistently told me:

“The issue isn’t time; it’s that the feeling of the night can’t be replaced.”

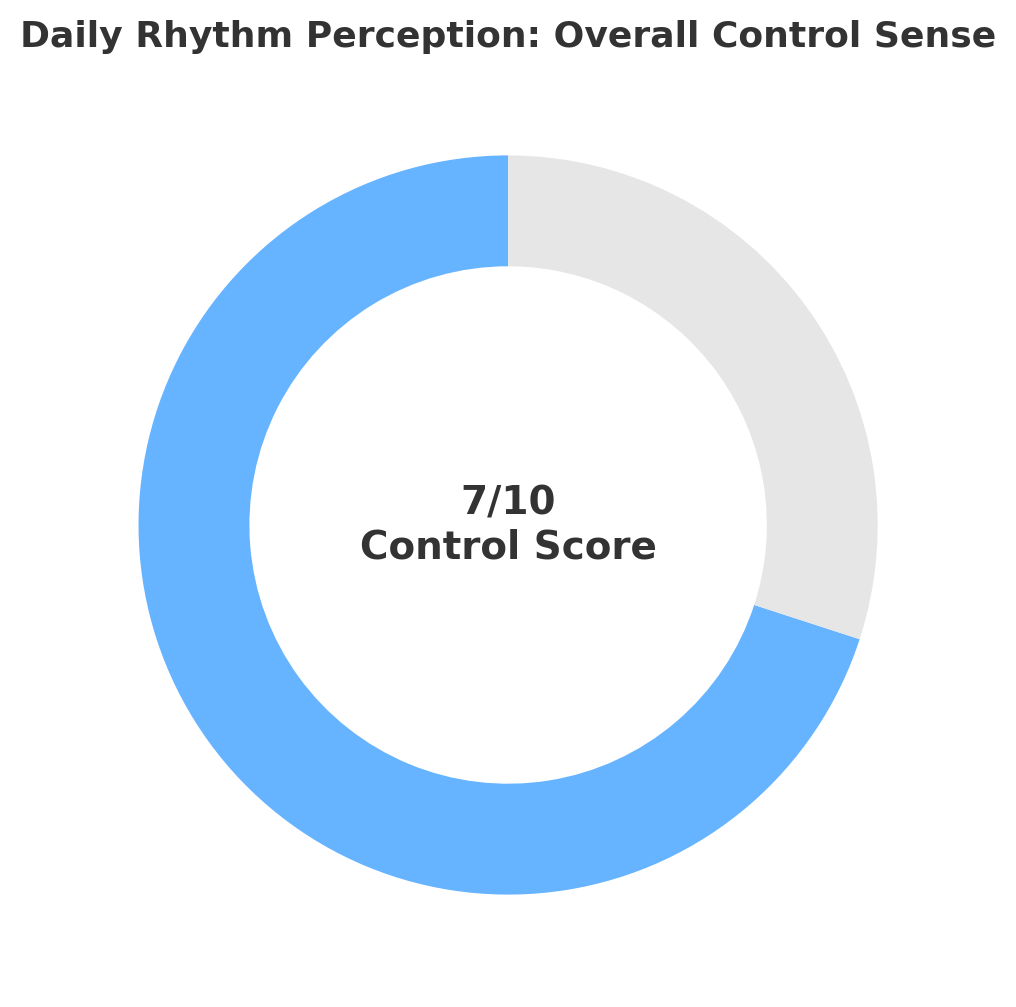

Intervention 2 — Rhythm Perception Card:

Allowing participants to see their own daily rhythm

Participants recorded their emotions, energy levels, stress, and sense of control. These records uncovered what their daytime usually hides: exhaustion, pressure, and the emotional intensities that accumulate at night. The diaries let me enter their actual lived rhythm.

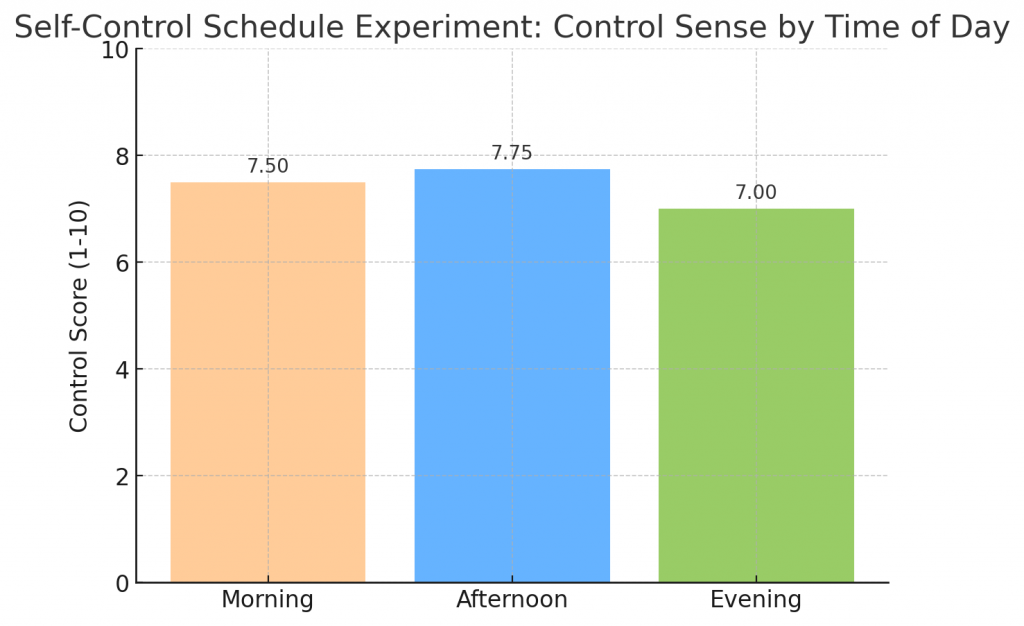

Intervention 3 — Autonomy-Based Routine Planning:

Helping participants co-create autonomous daily rhythms

We co-designed personal schedules to introduce meaningful autonomy during the day. This helped me understand how genuinely self-chosen activities reduce the urge for night-time compensation. One participant told me:

“I didn’t know I could actively choose my rhythm during the day. I thought I could only be arranged.”

This moment showed me how intervention design can reshape behavioural pathways.

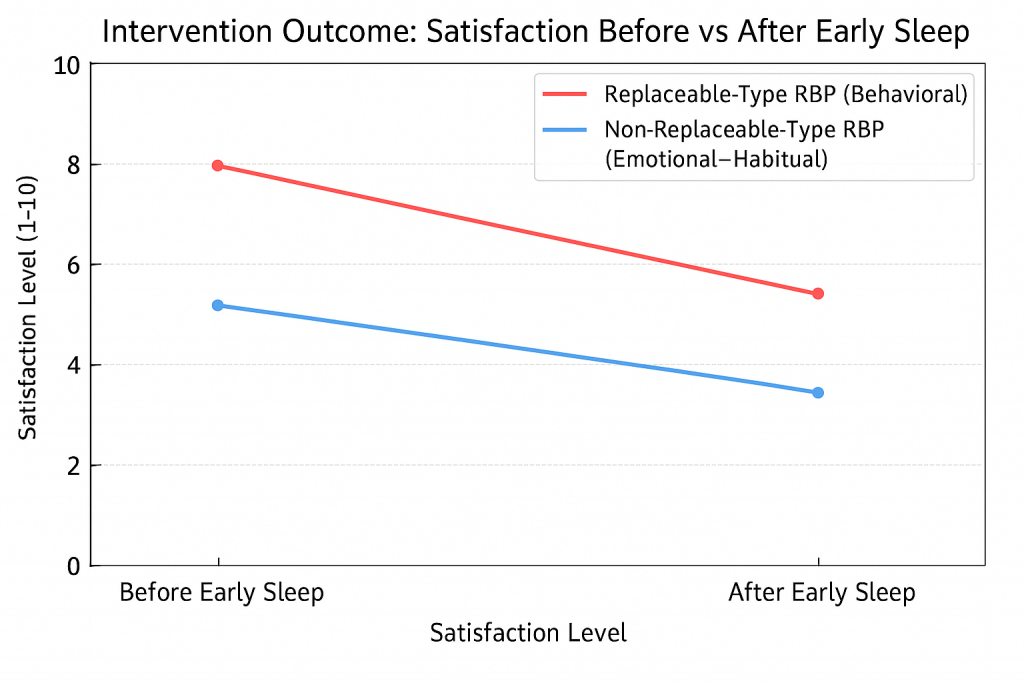

Intervention 4 — Time Perception Manipulation:

Secretly shifting participants’ bedtime forward

In this final experiment, I advanced participants’ sleep time without their awareness. Two clear types emerged:

Replaceable type: felt satisfied even when going to bed early

Night-dependent type: felt unsatisfied, even with the same activities performed earlier

Through these interventions, my role alternated between observer and design researcher, deepening my engagement with participants’ lived experiences.

3. Everyday Research: Conversations, Emotions, Rhythms

Throughout the project, I engaged in long conversations with participants,not only about their late nights, but about identity pressures, emotional tension, and the feelings they can only confront at night. Several participants said this was the first time they had spoken openly about these emotions. This helped me realize that research is not only about collecting data,it is also about witnessing emotional realities.

I visualized participants’ diaries, emotional curves, and rhythm patterns. When participants saw these visualizations, many realized that Revenge Bedtime Procrastination was not merely a sleep issue but a manifestation of deeper psychological needs. The participants’ understanding deepened, and it also enabled me to have a more systematic understanding of the relationship between rhythm, emotion and behavior.

4. How This Research Has Changed Me

As the research progressed, I shifted from being simply an observer to becoming:

a companion;a listener;a designer of interventions

This transformation made the process more honest, ethical, and meaningful.

Working with participants to uncover the mechanisms of Revenge Bedtime Procrastination taught me:

how to break down a phenomenon into mechanisms

how to design a process, not just an outcome

how to listen, accompany, and facilitate reflection

how to situate myself within a cross-disciplinary landscape

This project not only enriched my research abilities but also reshaped my perspective on human behaviour and wellbeing.

Leave a Reply